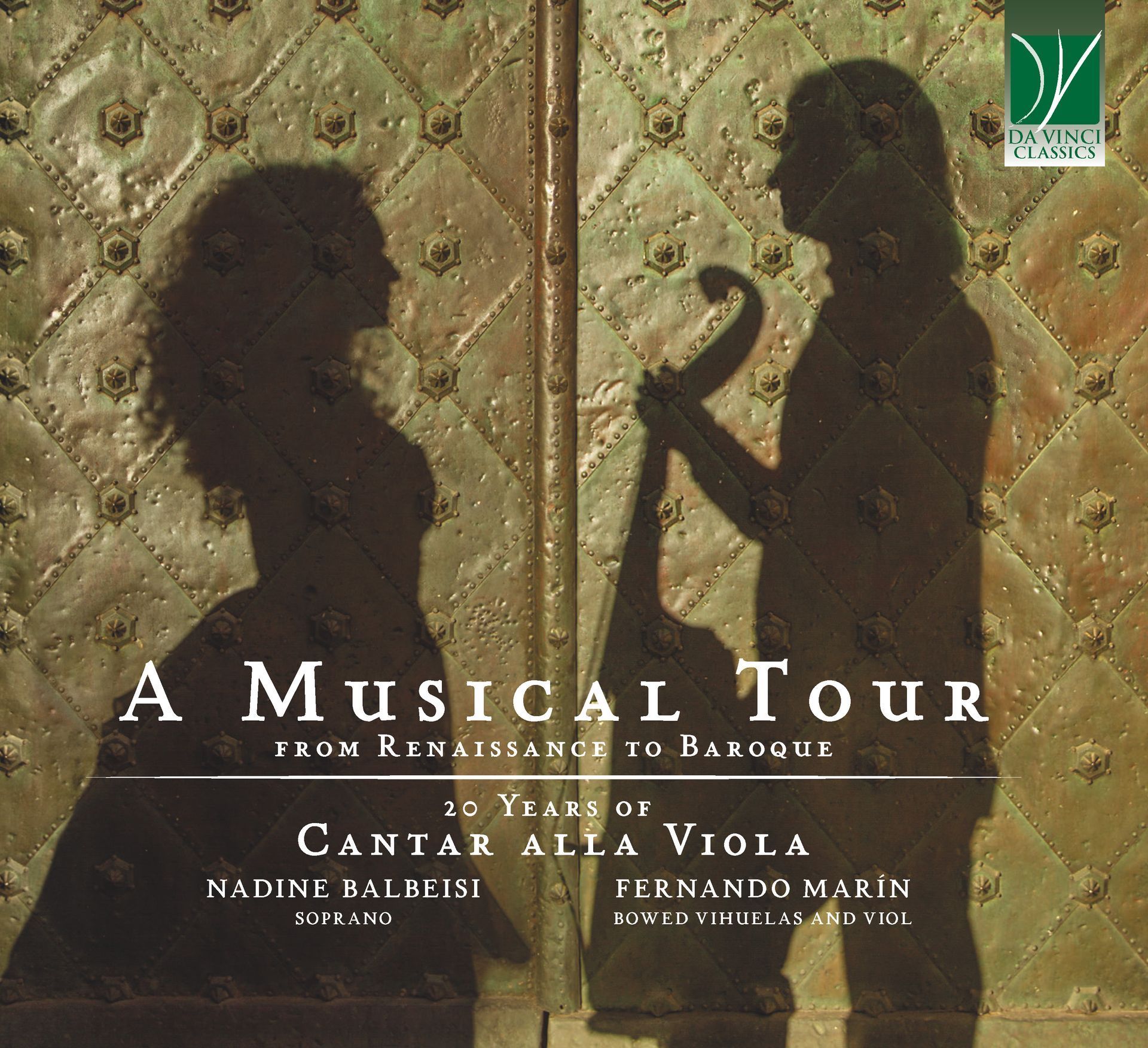

Cantar alla Viola

Nadine Balbeisi – soprano

Fernando Marín – bowed vihuelas

Label – Davinci Classics

A Musical Tour

From Renaissance to Baroque:

20 Years of Cantar alla Viola

«Ich komm aus fremden Landen

und bring euch viel der neuen Mär»

(I come from foreign lands and bring you many news)

The pinnacle of Renaissance music and its practice was forged in an incessant coming and going, a constant journey of musicians and musical chapels through courts or noble, royal, ducal, and papal houses throughout Europe. From the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, musicians from far and wide gathered in Flanders to catch up on musical material, sent by kings, dukes and counts from all over Europe. Some musicians called these gatherings “the schools.” These meetings served, in addition to learning things about their Art, as a kind of market for musicians. Musicians from the Franco-Flemish regions brought their polyphonic compositions and most refined musical skills to other countries like Italy or Spain.

Instrumentalists in the fifteenth century played from memory or improvised, making variations of themes and polyphonic works in vogue, which is why they rarely left written scores. This musical practice is reflected in the chronicles of the time. The court of Burgundy served as a model for the rest of Europe. From a group of chamber instrumentalists at the service of the duke, the duo of Cordoval and Fernandez stood out with their lutes and bowed viols. They are mentioned in the chronicle of a banquet held by the Duke of Burgundy in 1454.

Johannes Tinctoris, in his treatise De Inventione et usu Musicae, affirms that the bowed viol (viola cum arculo) was a Spanish invention (hispanorum) also mentioning that although the viola sine arculo (without bow) is frequently played in Italy and Spain, the Germans are also known everywhere as experts in playing these bowed viols. Tinctoris describes having seen two “Flemish brothers,” Carolus and Johannes, in the city of Bruges interpreting polyphonic music on two bowed viols. One of the brothers divided the tenor’s cantilena on the rebec and the other the consonances on the viola, “alternately imitating each other with such grace and skill that it caused great joy, joy and affection to the spirit, ardently inflaming” the heart of the Flemish theorist.

CANTARE ALLA VIOLA

Accompanying song with stringed and bowed instruments was a common practice at the time of Renaissance humanism. Looking to revive ancient Greece, musicians accompanied verses of songs with bowed viols at banquets and meetings in houses and palaces such as the courts of the Dukes of Ferrara and Milan or the Medici and Este families. This practice of accompanying the voice with a viol (where the singer sang or recited one voice of the madrigal with the other voices played on the instrument) is also mentioned by Baldassare Castiglione in The Book of the Courtier (Il Cortegiano, Venice, 1528) as being one of the skills a good courtier should possess. According to Castiglione, of all the styles of music for a courtier to practice, the best was to sing with a viola (cantare alla viola) for it enables one to appreciate “all the sweetness” that is found in the solo voice. One singer can give more attention to the “fine manner and the melody” and a “grace” to the words that is not possible with many singers. One variant of this way of singing with a vihuela, which he considers to be the best, is the one ordinarily called “reciting,” which “adds to the words a charm and grace that are very admirable.”

An example of a madrigal set in tablature to be sung and played with the “viola” can be found in Sylvestro Ganassi’s treatise Lettione Seconda (Venice, 1553). His treatise mentions two illustrious men of the period, Juliano Tiburtino and Lodovico Lasagnino Fiorentino, who were very skilled and great in this manner of playing. Such a practice was realized in a way that one added or took away that which enabled the adaptation of the madrigal to accommodate the practice of the viol. The strings “that are the most consonant are able to sustain the harmony as well as the texts and such.” If one would like to perform a composition of four or five voices, playing four parts and singing the fifth, Ganassi offers a possibility in which it would be necessary to “accommodate” oneself with a bow, which is longer than an ordinary one and with bow hairs that “can be less tensed,” in order to adapt more easily to the strings, which are needed for the consonances.

One of the most important characteristics of performing Renaissance and early Baroque music is the use of Rhetoric and the expression of the affects contained in the text. Our interpretation is inspired by Ganassi’s recommendations on how to imitate the voice with a bowed instrument (Regola Rubertina, Venezia, 1542). According to the meaning of the text and depending on whether the music is cheerful or sad, one should strike the bow alternating forte and piano, or in a “mediocre” way in the latter case. Ganassi compares the viol player to an orator who, “with the boldness of exclamation, gestures and movements” must always try to imitate laughing, crying and all “affects put into the music through the words” that may be in the text. In order to create the effect of sad or “afflicted” music, one must move the bow in a slurred way, even shaking the bow and the left hand in a way of “making a movement and giving spirit” to the instrument relative to that which the music requires. Ganassi warns that, as well as an orator, the player will “not play happy music with a slurred bow and similar movements belonging to sad music.” On the contrary, “happy music should be struck by the bow in a way proper to such music.” Diego Ortíz (Tratado de Glosas…, Roma, 1553) offers similar tips on how to play “sweetly” and change the sound according to the mood suggested in the music.

In this program we take a journey through Renaissance and early baroque music to celebrate twenty years of our duo Cantar alla Viola – founded in Cologne (Germany) in 2004 and presented at the Van Vlaanderen-Antwerpen Festival in Antwerp (Belgium) in 2006. We perform a selection of representative pieces of our repertoire arranged for voice and bowed viol, including Madrigals and songs by Italian composers such as Constanzo Festa, Settimia and Francesca Caccini, villancicos by the Spanish Francisco de Peñalosa and Juan Blas de Castro, English songs and airs by Robert Jones, William Corkine and Henry Purcell, including German arias by Jacob Kremberg with lyra viol tablature. With great technical refinement, the strings of the violas imitate the sweetness of the human voice, and the song is woven with skillful mastery between the voices of the polyphony, resonating with the delicacy of the texts.

The criteria for the interpretation of the musical pieces are selected in order to reach the highest historical accuracy. Our product is the result of intense and lengthy research, covering aspects such as historical pronunciation, the expression of affections and musical rhetoric. The instruments used in our performances –vihuelas de arco and Renaissance viols–, are historical models of the time, contextualized with the different periods of the repertoire, and built by Fernando Marín following the manufacturing methods and using materials of the time. All the strings used are made of natural gut, which allows an optimal mix of timbre with the voice. We hope you enjoy this album.

Fernando Marin © 2024